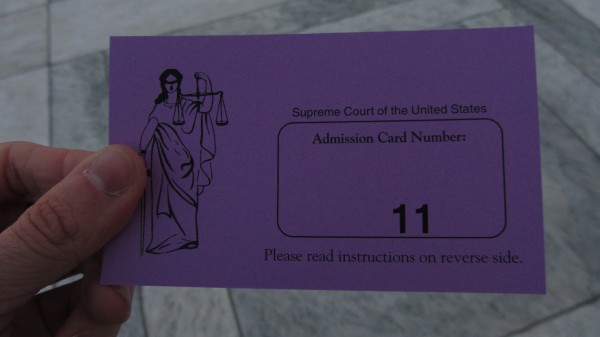

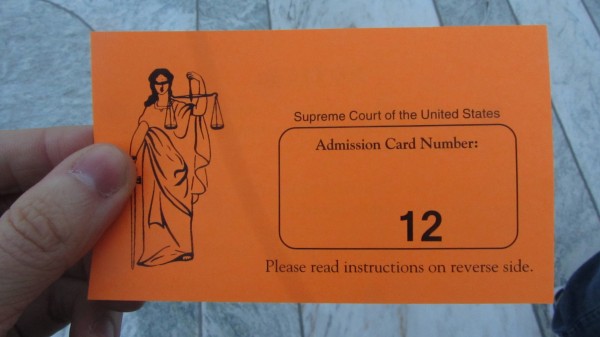

Now the second, final argument this trip. (There are other arguments this week, some interesting enough to attend. But I ran out of time to prepare for them or attend them.) Holt v. Hobbs is much simpler than Heien v. North Carolina, because one side’s arguments are “almost preposterous”. So this post is (slightly) breezier.

This line was a bit different from the Heien line: more people attending for (this) argument, fewer people present simply for opening day. The line was possibly less talkative (and I still had briefs to read, although I never intended to read all twenty-one [!] of them), but there were still good discussions with local law students, the author of one of the amicus briefs (which I naturally read standing in line), and others. Good fun again.

Gregory Holt and his would-be beard

Gregory Holt is a Muslim inmate in the Arkansas prison system. (He actually goes by Abdul Maalik Muhammad now; Gregory Holt is his birth [legal?] name. News stories and legal discussion refer to him as Holt, and in some sense I want this in that corpus, so I use Holt here.) Holt interprets Islamic law to require he have a beard.

Allah’s Messenger said, “Cut the moustaches short and leave the beard (as it is).”

A small request. Reasonable? Quoting the ever-colorful Justice Scalia in oral argument, “Religious beliefs aren’t reasonable. I mean, religious beliefs are categorical. You know, it’s God tells you. It’s not a matter of being reasonable.” Reasonable or not, a beard isn’t an obviously dangerous request like, “My religion requires I carry a broadsword.” And as a conciliatory gesture Holt moderated his request to a half-inch beard.

Arkansas: no beards

Arkansas doesn’t permit prisoners to grow beards (except to the natural extent between twice-weekly shaves). There’s an exception for prisoners with medical conditions (typically burn victims), shaving only to 1/4″. But no religious exceptions.

Arkansas’s justifications are three. A beard could hide contraband. A bearded prisoner can shave to disguise himself, hindering rapid identification and perhaps aiding an escape (see The Fugitive). And it’s a hassle measuring half-inch beards on everyone.

The law’s requirements

Twenty-odd years ago, Holt would likely have been out of luck. Turner v. Safley permitted regulations “reasonably related to legitimate penological objectives”. And Justice Scalia’s Employment Division v. Smith says that as a constitutional matter, generally-applicable laws may burden religious exercise, with objectors having no recourse. It’d be an uphill slog getting past the no-beard rule.

But in the mid-1990s to 2000, Congress near-unanimously statutorily protected some exercises of religion, even against generally-applicable laws. (Lest it be thought this was protection specifically, or only, of Christian beliefs: the original motivating case was a Native American group that used a hallucinogen for sacramental purposes.) In particular Congress enacted the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act (RLUIPA, usually “ruh-loo-pah”), stating:

No government shall impose a substantial burden on the religious exercise of [a prisoner], even if the burden results from a rule of general applicability, unless the government demonstrates that imposition of the burden on that person—

- is in furtherance of a compelling governmental interest; and

- is the least restrictive means of furthering that compelling governmental interest

And “religious exercise” is later defined as:

The term “religious exercise” includes any exercise of religion, whether or not compelled by, or central to, a system of religious belief.

Now, prisons may regulate in pursuit of normal prison aims. But regulations can’t “substantial[ly] burden” a prisoner’s “religious exercise”, regardless how important the exercise is(n’t) in the prisoner’s belief system, even if the regulation is general and doesn’t target religion — unless the government demonstrates the regulation satisfies a “compelling interest” that can’t be addressed less restrictively. This phrasing comes from strict scrutiny: the strongest form of review American courts apply to laws. Unlike the Turner/Smith regime, these requirements have teeth.

Evaluating Arkansas’s no-beard rule applied to Holt

As a threshold matter, Holt must wish to engage in “religious exercise” that is “substantial[ly] burden[ed]”. Once Holt claims the belief, courts won’t second-guess it. They will consider whether the belief is sincere: no opportunistic exception requests for unwarranted benefits. But no one contests the sincerity of Holt’s beliefs. If Holt refuses to be shaved, he’ll suffer various disciplinary actions and bad consequences: “loss of privileges, punitive segregation, punitive work assignments, and loss of good-time credits”. Certainly a substantial burden.

Now Arkansas must demonstrate — with evidence, persuasively — both a compelling interest, and least restrictive means. Put another way, does Arkansas’s regulation pass strict scrutiny?

Arkansas’s claimed interests are “prison safety and security”. But a no-beards rule only marginally advances these goals, and “the government does not have a compelling interest in each marginal percentage point by which its goals are advanced.” Arkansas’s interest must be more specific: an interest specifically in no beards.

It’s hard to say Arkansas has a compelling interest when the rules in forty-odd prison systems nationwide, and various penal code recommendations, either impose no restrictions on beards among prisoners, or would allow Holt his 1/2″ beard. Arkansas is an outlier. And Arkansas’s medical exemption undermines the argument that no beards must apply universally (compelling interests often brook no exceptions). Similarly, Arkansas can’t use the least restrictive means when forty jurisdictions use even less restrictive means.

Arkansas might justify their policy through unique local experience. But Arkansas concedes “no example” of anyone hiding contraband in a beard. (With the “caveat” that “Just because we haven’t found the example doesn’t mean they aren’t there.” A strong argument!) Disguise arguments could be addressed by taking multiple pictures (as other systems do). And measuring the few inmates requesting religious exemptions wouldn’t be much harder than measuring medical-exception beards.

Arkansas could “demonstrate” strict scrutiny is satisfied by providing evidence of evaluation and reasoned rejection of other states’ policies. But Arkansas previously admitted it considered no other systems (eliciting an acerbic suggestion to try “the common practice of picking up the phone to call other prisons”).

Arkansas could argue that Arkansas’s system, that houses many prisoners in barracks and not separate cells, justifies no beards. But such systems exist elsewhere, and no beards applies in Arkansas’s non-barracks prisons.

In short, Arkansas has demonstrated neither a compelling interest, nor least restrictive means, and it has done so presenting no evidence. Ouch.

In lower courts

An obvious question: why must Holt fight this in court if he’s so obviously right? Basically, a few lower courts are giving far too much deference (a word found in legislative history but not in the statute) to the mere assertions of prison officials, without requiring them to “demonstrate” much of anything. The magistrate judge described officials’ claim that Holt might hide something in his half-inch beard as “almost preposterous” — just before deferring to those claims. Courts below the Supreme Court similarly gave too much deference to prison officials’ bare assertions unsupported by any data.

At the Supreme Court

One indicator of lopsidedness here is the brief count, and authors, on each side. Holt has seventeen other briefs on his side, representing a wide variety of interests: Jewish, Christian, Islamic, Hindu, Sikh, American Indian and Hawaiian, former prison wardens, former corrections officials, Americans United for Separation of Church and State (whose brief, incidentally, is interesting but quite surpassed by later events), sociologists, and the United States government (and others). The authors include a who’s-who of religious freedom organizations. Arkansas has one brief on its side: from eighteen states, who don’t defend Arkansas’s policy as much as try to preserve deference as an element to consider (presumably so those states’ prison systems can be run with a freer hand).

The Court accepted this case in unusual circumstances. Holt filed a hand-written petition requesting Supreme Court review, through a special system not requiring him to pay filing fees from non-existent income. Such petitions are almost never accepted. (Holt basically won the lottery. That said, when I read his brief after the case was accepted, the form was unusual, but the discussion and presentation seemed orthodox.) It’s pretty clear the Court accepted this case to lopsidedly, probably unanimously, overturn the Eighth Circuit. The Supreme Court doesn’t take cases to correct errors, but that’s what they’ll do here.

Oral argument

The argument questions roughly ran in largely three veins: pondering deference, drawing a line, and almost mocking Arkansas’s arguments. Holt’s counsel faced difficult questions, but not skeptical questions.

Deference

First, what does deference (if it even matters — the term appears only in legislative history, not in the law as enacted) look like in the context of strict scrutiny? These are somewhat contradictions in terms. Yet the Court somehow must make sense of this.

Line-drawing

Second, while beards are easy to decide, other issues (Sikh turbans that actually can conceal things, for example) will require different considerations. How can the Court provide general guidelines to address these situations? The Court doesn’t want to be in the business of reviewing every prison official’s (better-“demonstrated”) decisions. (Scalia bluntly put it this way: “Bear in mind I would not have enacted this statute, but there it is.” Recall he wrote Employment Division v. Smith, shutting off constitutional religious exemptions from generally-applicable laws. Something to remember any time Scalia’s stereotyped as reflexively pro-religion.) But Congress opened up that box, so courts have to live with it.

Almost mocking questions

Arkansas’s position is not easily defended. Not surprisingly, then, questions and comments almost made fun of Arkansas’s position. To the assertion that “Just because we haven’t found the example doesn’t mean they aren’t there”, Justice Breyer replied, “There are a lot of things we’ve never found that might be there and I’ll refrain from mentioning them. You see them on television, a lot of weird programs from time to time.” (Presumably referring to things like Sasquatch, the Loch Ness Monster, Ghost Hunters, and similar.) And later, Justice Alito proposed an alternative means of detecting beard contraband: “Why can’t the prison just…say comb your beard, and if there’s anything in there, if there’s a SIM card in there, or a revolver, or anything else you think can be hidden in a half-inch beard…” (emphases added). Both lines made the audience erupt in laughter.

Why Arkansas fights

It’s unclear to me why Arkansas is still arguing. They won in lower courts. But once the Court granted the in forma pauperis petition, Arkansas should have folded. The law is too clearly against them, and this Court won’t give them a pass. Arkansans should be outraged that their state is wasting taxpayer money to defend this system. (And on the policy’s merits, outraged at the petty bureaucratic nonsense at best, and bigotry at worst, it represents.)

One plausible, potentially upsetting, explanation is provided by former prison wardens: “Political Considerations May Underlie Prison Officials’ Resistance to Accommodations of Religious Practices.” These wardens had been sued (and lost) in various cases cited in briefing, and they candidly admitted that their positions were partly attributable to “political realities”.

Conclusion

Arkansas will lose. The only remaining question is how. (And as before, if I’ve made any mistakes in this discussion, please point them out.)