September 12

(5.0; 1330.9 total, 843.1 to go; -10.0 from pace, -109.1 overall)

After this brief interlude with family, it’s time to get moving again. Mom makes some effort to get me to not hike for another day, but I’m somewhat leery of taking two zeroes as I’ve never done so before, and I dig in my heels. I’m back on the trail shortly after 11:00.

It’s only five miles to the first shelter, and strangely I complete them at a three-miles-an-hour pace despite it not being the afternoon, eating a Granny Smith apple as I hike. Mm, delicious absurdly heavy foods…. I arrive at the shelter to unexpectedly find someone there — Smoothie again! He’s now hiking for a few days with a girl he met at a yoga class in Delaware Water Gap. I stop to eat and lighten my pack, pulling out a loaf of raisin bread to attack. Between the weighty pack and another southbounder I’m not in much of a rush to get moving again; when the Honeymooners walk up, my plans to hike further today vanish. Four southbounders all in one place — it’s been ages since this has happened to me.

But wait, there’s more! In walks a hiker with her father, and she looks familiar — turns out it’s Kat, whom I met at Wintturi Shelter back in Vermont. I’d thought she was a northbounder, but it seems she’s really flip-flopping around Waynesboro, hiking south for a few days with her father before he heads back to work. So, all total we have five different thru-hikers here for the night, four of them true southbounders — crazy…

The rest of the day is pretty lackadaisical. The only memorable bit occurs while I’m making dinner, something Knorr-ish as usual. Smoothie’s hiking companion, a vegetarian, looks aghast at the amount of sodium in my overall meal; she calculates somewhere around 2000mg total. I take a look and see she’s wrong — one of my food items is actually two servings, not one. Mm, sodium…

September 13

(15.8; 1346.7 total, 827.3 to go; +0.8 from pace, -108.3 overall)

Today’s goal is a shelter about twenty miles south, but my hiking pace just isn’t feeling up to it,. It’s starting to get pretty dry, and water is somewhat scarce. I hike south in the latter half of the mob moving south: Honeymooners in front, Smoothie and girlfriend next, me, then Kat and her dad, in rough order. I last see Kat maybe a dozen miles into the day when I stop briefly at a road crossing to eat an apple; I assume they’re heading to the next shelter a few miles south, but after I leave it sounds like they made a very abrupt decision to spend the night in town; combined with my pace this is therefore the last time I see them.

I travel the next several miles to Maupin Field Shelter, arriving maybe around 17:00. I plan to only briefly stop to fill up on water, but a certain lack of energy, plus the meagerness of the water source, mean it makes more sense for me to stop for the night here. The shelter is initially occupied by someone who’s set up his tent in it; I don’t mind this when a shelter’s empty enough, but it’s not here. Eventually enough people show up that I manage to argue the owner into moving into a perfectly serviceable campsite instead. Besides Smoothie and companion there are a couple random backpackers and one flip-flopper named Toad. Toad’s from Pennsylvania somewhere around Pine Grove Furnace State Park, and he started near there June 7, hiked north, then flipped back to hike south again. He carries a rather large Jetboil stove with him as a luxury item. The Honeymooners are characteristically efficient in their hiking and thus end up at Harpers Creek Shelter about five miles south, rather than this one. (They later express surprise I didn’t make it there; I do tend to be a bit erratic in my pace at times.)

Even later yet, however, another backpacker arrives, and from our (Smoothie, Toad, me) first sight of him alone it’s clear he’s a very special hiker. He’s lean and thin, he’s hiking quickly with poles pumping, and his backpack — if you can call it that — isn’t much more than Camelbak-sized. (He tells us his base weight — what he always carries, then additionally supplemented with food and water, is something like four pounds. Total, he’s at about a dozen.) This guy’s someone we’re going to see tonight and never see again. Brian (no trail name, nobody sees him long enough for him to pick one up) isn’t just a crazy thru-hiker, he’s a yo-yo. (That’s a technical term: he’s hiking the Trail first one direction, then the other, so south to north, then north to south, all at once, for a total of 4352.4 miles by his count.) You might think he runs when he hikes, but really he just hikes at a good pace without stopping. He hikes maybe 2.8 miles an hour, which is actually slower than my comfortable top pace when I reach it. I stop way more, and I don’t always hit that pace, and start to stop I probably am out shorter periods of time, so overall I travel comfortably less distance than he does, and I’m not really a slouch by thru-hiking standards myself. We see him tonight and tomorrow morning, then never again. (One last comparison to illustrate the enormity of his hiking prowess: he takes 24 days to hike the remaining 827.3 miles, ending October 7; I take 42 and end October 25.) It’s amusing to contemplate a pace like that, but I couldn’t do it over the long haul. Nevertheless, Hike Your Own Hike.

September 14

(20.5; 1367.2 total, 806.8 to go; +5.5 from pace, -102.8 overall)

I get a good start on the day today with an early (for me) departure, which I then promptly squander/invest in stopping at the following vista for awhile to enjoy the view and eat an apple:

The nearby mountain in that picture is The Priest, and my hiking today goes down, then up and over it. It’s the first elevation above 4000 feet since Massachusetts: the long stretch of relative flatness is ending. Still, the ascents aren’t tiring or steep like Maine or New Hampshire were. I’m sure at least some are comparable, but for the most part I barely notice them as requiring extra physical exertion: it’s where the trail goes, and thus I follow it. It’s so nice to be in thru-hiker shape. As you can see I’m at a bit of an elevation for that picture, and I stay up for a little longer before starting the descent all the way to the bottom of the valley (in preparation for the ascent right back up the other side 🙂 ).

The descent from the heights is great as I pass by Harpers Creek Shelter, refilling on water from the creek. South and down from there I pass over the Tye River and a road crossing, then it’s up the other side again. By now it’s mid-day, and the physical exertion plus beating sun make it pretty hot. The view from the top is great:

Past there it’s only a mile or so, descending to a slightly lower elevation, to reach The Priest Shelter where, as usual, I stop to read the register and get a bite to eat. This register is particularly memorable for being placed by northbounder Don Juan, who declares that entries must, being near “the priest”, make a confession of some sort; it makes for entertaining reading. My “confession”, I’m certain, some would call a conceit: I confess that I don’t think someone who hikes the Trail in segments over extended time deserves to be called a thru-hiker. (The ATC explicitly recognizes anyone who walks or makes a good faith effort to walk the entire trail, ignoring timing, carrying of supplies or not, &c. However, they recognize with the moniker “2000-Miler”, in reference to the original expected length of the Trail, and they don’t distinguish anyone as a thru-hiker.) To me a thru-hike implies, well, that you began the hike, hiked through the trail, and completed the hike, all in one go. You didn’t hike part, stop, then hike more of it some vastly different time, and so on until completion, you started hiking and didn’t fully return to non-hiking life until you’d walked every bit of the trail. Even flip-floppers kind of leave me feeling a little weird due to “through” being a little twisted geographically, but they do hike the entire thing, in one go, without stopping, so it’s enough for me. A section hiker still can claim to have walked the entire Trail, which is certainly no mean feat! He just shouldn’t (by my opinion, take it or leave it) imply he hiked it all at once by calling it a thru-hike. (As I’ve noted before, I’ll make one exception to this rule: the northbounder K1YPP, who claims his medically-required triple-bypass surgery caused him to take “three hundred zeroes”, for the sheer audacity of the claim 🙂 .)

At this point Toad catches up to me and stops for the day. It’s still before 17:00 or so, I haven’t done enough mileage to be above pace yet, and it’s not that much further (couple hours or so) to get to Seeley-Woodworth Shelter, so I head on. Smoothie and the girl he met are jumping off the trail again at a road crossing near here, so I’m pretty sure I’ll be alone at the shelter for the night, which does turn out to be the case. Seeley-Woodworth is most memorable for its spectacular water source: a piped spring with excellent clear water practically gushing out of it, the best water source on the entire Trail in my opinion. The shelter has a bag of wild apples hanging from one of its vertical supports, and I avail myself of a few. I still have Granny Smith apples from the store (have I mentioned how weight-unconscious a backpacker I am?), but wild apples have a different flavor — stronger, but not necessarily better, and variety is good. Also, in a bizarre occurrence, I find what I think is a tick on one of my toes tonight, in a location so far within boot and sock that I have no idea how it could possibly have gotten there.

Future plans now begin to impose upon my hiking schedule, as I consider when I’ll reach where, with whom, and so on. I have enough food to reach Daleville, ninety miles south, and ideally I’d like to stay there for the night. Unfortunately, since I’m near the front of the southbounder pack, and as Daleville doesn’t have hostel-style accommodations, doing so could be expensive. There aren’t any southbounders that close in front of me with whom I could split a room, and I’m not aware of anyone sufficiently close behind, either, that’s likely to hike far and fast enough to catch up. (Smoothie, as far as I can tell, doesn’t usually hike the sort of days I’ll be hiking over the next few days, although he’s certainly capable of doing so.) Further compounding the problem is that Daleville’s at the start of a 26-mile section of trail where camping is only permitted at a few specific sites, the first being nine miles in — so resupply in Daleville without staying longer means I have to reach it by midday. Camping between here and there means the most plausible schedule involves me hiking 24, 25, 24, and 18 miles the next several days (and maybe nine more the last day if I can’t figure out a way to stay in Daleville without spending more than I want to do so), so it looks like my schedule is going to be fairly inflexible for the next several days. None of the mileage is excessive, so it won’t be too much trouble, but it does mean I probably will push late if necessary to make a planned stop even if I’d rather stop earlier.

In the end I decide I’ll act in anticipation of something happening that permits me to spend a night in Daleville. I have no idea what that might be right now, but if worst comes to worst I’ll end up resupplying in Daleville and heading on for a twenty-seven mile day through it. With scheduling considered and resolved as best as I can with what knowledge I have now, I head to sleep on a very windy night.

September 15

(25.3; 1392.5 total, 781.5 to go; +10.3 from pace, -92.5 overall)

It’s up and out and hiking again, with a few wild apples stashed in my pack. The morning is perhaps more sluggish than usual; around noon I stop on a hillside for lunch and find Toad’s caught up to me. He’s thinking of doing a crazy long day today, just for the heck of it, since he didn’t do the semi-traditional Four State Challenge when he was passing through Harpers Ferry. If that happens, he’ll spend the night at Johns Hollow Shelter, 34.1 miles south of where I started today and 41 miles south of where he started today. Maybe I’ll try another super-long day at some point (that twenty-four hour challenge is particularly tempting), but that day isn’t today. At about twenty-five miles away, Punchbowl Shelter will make a solid, non-crazy day.

Along the day goes, traversing ridges and eventually descending to U.S. 60. About ten miles one direction (I’m in the middle of a ridge with nothing around) is a city, but I’m all set for another eighty miles or so, so I’m just passing by. While doing so, however, I take advantage of the small picnic area there to throw away trash — nothing better than trailside trash cans.

Past the road the trail remains flat, paralleling a decrepit creek with a few crayfish in sight, all the way to Brown Mountain Creek Shelter. The valley seems to be some sort of historical hike; there are signs along the way pointing out that a community of freed slaves lived in the area from after the Civil War until around 1918, illustrating way of life, pointing out remnants of buildings, and so on. Somewhere around here I briefly catch up to Toad again, but my slightly less energetic pace means he quickly leaves me behind again. I hike the last 9.5 miles to Punchbowl to arrive around dusk. As I’d expected the Honeymooners are here, and strangely enough, Toad is too — I’d figured he’d have moved on given his goal of 41 miles for the day, with 8.8 to go. We all talk briefly as I unpack food and get water from the nearby small pond, and Toad prepares to head back to the trail for some quality night hiking.

This shelter’s most memorable for its association with Ottie Cline Powell, who is — I am not making this up — a four-year-old ghost claimed by some to haunt the shelter. In November 1891 Little Ottie’s teacher sent his class outside to gather firewood to keep the schoolhouse warm, after winter’s first snow and in anticipation of more cold weather to come; the other students returned, Ottie did not. His body was eventually found by accident months later atop Bluff Mountain (over which the A.T. travels tomorrow) a full seven miles away. Surely it was a different time, when four-year-olds were sent to gather firewood like this…

Claims of haunting notwithstanding, I find the shelter no more or less eerie than any other, and I see no sign of menacing Little Ottie at any time.

September 16

(25.1; 1417.6 total, 756.4 to go; +10.1 from pace, -82.4 overall)

The Honeymooners leave well before I do, and my typically slow morning pace means I don’t see them for the first half of the day. Mostly the trail sticks to the ridge; at one point I look down toward the upcoming James River, over which the trail crosses, to see a train passing by. It’s far enough away that I can’t hear the train, and its apparent glacial pace reinforces just how high and how far from it I am. I take a couple pictures, but the distance is too great and the camera’s too weak to get anything decent. From here it’s a descent down to Johns Hollow Shelter. I lack much energy or enthusiasm, so I stop for lunch; my entry in the register is a very rough recreation of the “Lunch break! Lunch break!” scene from A Charlie Brown Christmas (apologies to Charles Schulz noted explicitly in the illustration). It seems Toad made it here last night, found in the register that the northbounder Don Juan from this year had somehow managed to become caretaker of a house in the area for a brief period of time just about now, and was opening it up to southbounders — so presumably he’s there relaxing after a forty-miler now. There’s no sign of the Honeymooners, who probably came through hours ago; I hope they stopped, if only to experience the amazingness that is the privy at this shelter. Cedar wood, hand rails, handicap-accessible-sized, it’s a real thing of beauty.

Fooded up from lunch, I head on again. It’s only a mile and a half or so to the James River, where I catch up to the Honeymooners. They’ve hitchhiked into town and eaten and resupplied, all in the ponderous time it took lazy me to get here. I definitely could make better time out here if I put some effort into it. But where would be the fun? Why restrict myself to a schedule of when and how long to hike each day, just to go a little further, a little faster? I pass them by and head across the James River Footbridge, the longest foot-travel-only bridge on the trail.

You can get a feel for the size of the bridge from this picture, which going from overhead views appears to be just over six hundred feet long. I understand the pilings were already there before the bridge was constructed, but even still, I have no idea how this bridge ever managed to get funding. I suspect I largely have my American readers’ knowing and gracious generosity (wink wink, nudge nudge, say no more!) to thank for this:

How did hikers travel this section prior to installation of the bridge? It looks like if you head around half a mile east you’ll hit U.S. 501, which travels south over the river, and which hikers could cross, then travel the same distance back along the river to reach the spot where the current footbridge’s south end is. Tedious and boring (and depending on the condition of the crossing, plausibly dangerous), and I can certainly see why you’d want something else instead, but I can’t help think that, for the number of people who go across it and for the appreciation of it they have, it wasn’t worth the costs as they were likely apportioned. (Subsequent searching reveals a brief overview of the bridge’s genesis which suggests that the bridge owes its existence to a few hundred thousand dollars in donations plus several times more state funding. It looks like the creators were moderately successful at funding it in non-coercive ways, which is a small comfort — plus it seems Virginia properly took on the cost of its own project, rather than trying to live off the federal dole.)

Now being in front of the Honeymooners spurs me to hike more quickly, and I keep a brisk pace to Matts Creek Shelter. I stop and say hi to the guy already there and write something in the register. This register also contains the most brilliant combination of an entry from Thought Criminal (first noted in registers back in mid-Vermont) and a couple responses (a postscript in the first photo, an unknown person’s side note in the other). Beware: Authentic Marxist Gibberish ahead! 😀

Thought Criminal: "May 30, 1984. Thought Criminal pitching my Duermo Baggie Transnational Corporation sweatshop factory labor produced Casa de Silnylon next to the creek for the night." Red: "ps. I love my Duermo Baggie"

A further note: Duermo Baggie ("sleeping bag" in Spanish) as such doesn't exist according to Google, so I'm not sure how to interpret his rant against it.

A followup entry by Thought Criminal:

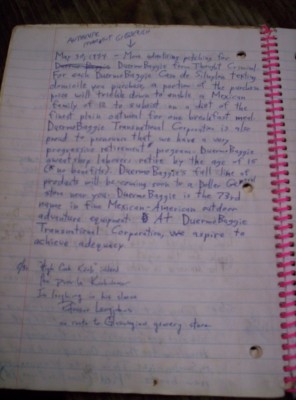

"May 30, 1984 - More advertising pitching for DuermoBaggie from Thought Criminal. For each DuermoBaggie Casa de Silnylon tenting domicile you purchase, a portion of the purchase price will trickle down to enable a Mexican family of 12 to subsist on a diet of the finest plain oatmeal for one breakfast meal. DuermoBaggie Transnational Corporation is also proud to pronounce that we have a very progressive retirement* program. DuermoBaggie sweatshop laborers retire by the age of 15 (* no benefits). DuermoBaggie's full line of products will be coming soon to a Dollar General store near you. DuermoBaggie is the 73rd name in fine Mexican-American outdoor adventure equipment. At DuermoBaggie Transnational Corporation, we aspire to achieve adequacy."

Someone else has written "AUTHENTIC MARXIST GIBBERISH" with an arrow pointing at the entry.

I move along just as the Honeymooners catch up to me, as I keep ahead of them for a little bit longer, but they catch up when I stop a couple miles south to refill water bottles from a small stream the trail crosses. From here we hike the next several miles together, following and curving along the ridges in the area. My mental distance counting notes that some of the claimed mileages near here are wrong, with the mistake being, as I recall it, that two segments’ distances are transposed. No worries — and it should have since been fixed in more recent Companions (whether by my notes at the 2009 Trail Days or prior to that, I don’t remember).

Shortly after this we reach Marble Spring, site of a spring and a campsite. It’s around 17:15 now, and we’ve hiked a solid 18.2 miles, so the Honeymooners stop for the day. There’s still plenty of daylight for me to get to Thunder Hill Shelter without hiking in too much darkness, which puts me that much closer to the people ahead of me that I’m attempting to catch (most immediately Grettle, Mango, Cubby, Spoon, and Santana), and on pace to make Daleville at a reasonable time, so I continue on after refilling on water.

The hiking goes ever so slightly more slowly now that I have no pace car to follow, but I still make good time. I pass by another apparent mileage anomaly, making two in the space of one day (in the space of several hours, even) — very strange. It’s getting later into fall, so I’m now starting to race against dusk when I hike past 19:30 or so, as this picture from Thunder Ridge Overlook demonstrates:

I’m only 1.4 miles from the shelter now, and as you can see darkness threatens, so I keep up a good pace to make it the rest of the way. Ten minutes or so before reaching the shelter I hear a crashing noise (in nighttime-level darkness) off to my right, which puts me on my guard for the possibility of there being active bears in the area. A short bit of hiking later finds me at the shelter, where I eat dinner and head to sleep in short order. Twenty-five miles: definitely a good day’s hike despite a somewhat slow start, and progress consistent with making Daleville in two days.

September 17

(23.6; 1441.2 total, 732.8 to go; +8.6 from pace, -73.8 overall)

I get a decent start today out of the shelter, leaving a little after eight. The morning is cool and slightly foggy and cloudy, if memory serves, as I head underneath The Guillotine toward Apple Orchard Mountain.

The mountain isn’t much of a mountain, but it’s still the highest point between Chestnut Knob, roughly two hundred miles south, and Moosilauke, slightly over 1000 miles north. There’s an old Air Force radar base atop it with a distinctive spherical radar dome, surrounded by fences with no-trespassing warnings, but otherwise there wasn’t much to see, so I kept moving along to Cornelius Creek Shelter, where I stop for a second to eat. The shelter’s reading material includes an Appalachian Trail guide from around 1992, and I crack it open to see how similar the trail and side features along the way were then to now. Running a hostel is a labor of love, and to be completely honest I’m not sure how one can actually make money on it, so it’s unsurprising that there’s a lot of changes on that front. I continue south to Bryant Ridge Shelter, perhaps the most architecturally significant shelter on the entire trail: it literally has three stories. The Companion suggests it sleeps 20; it could sleep many more if necessary (more still if people moved onto the lowermost floor’s porches, rather than restricting themselves to the “living” areas).

While I’m at the shelter, a hiker walks up, coming from the north. It turns out to be Cubby, another southbounder, who’s been ahead of me since the beginning of the trail, whom I now seem to have finally caught up with. He’s walking with little more than a day pack (possibly not even that), slackpacking south for the day, along with the rest of a group that’s been hiking together for, as I remember it, a bit under a thousand miles at this point: Grettle, Mango, Spoon, and Santana constitute the remaining members. Santana arrives as we sit, and Spoon follows shortly. Cubby and Santana depart shortly, as do I, but since neither is wearing a backpack I find myself unable to keep up with them without excessive effort. Spoon, on the other hand, is wearing a slightly more loaded day pack and has a pace just slightly faster than mine would be if I were hiking alone. The result is that I make excellent time as I hike with him the next ten miles or so to the road where he and the others are being picked up for the day. Along the way I get an update on current events: Lehman going under and the ensuing mass financial hysteria. When we eventually reach the road (I meet Grettle and Mango there, as they arranged the ride to pick the others up), I’m left with much to think about, if not much detail about which to really, deeply consider matters. The excellent pace of the last few hours means that I still have a good deal of daylight in which to hike to Bobblets Gap Shelter. Were I an hour earlier I’d probably even consider moving beyond that, but as it is dusk makes that unpalatable.

After I fill up on water from the creek just the other side of the road, I head along to the shelter, arriving around 18:15. It’s comfortably evening, but there’s plenty of daylight and time to eat (my meal for the night is potatoes with bacon bits, a fact I take pains to note after seeing Flashdance’s entry express a hunger for bacon) and read awhile before heading to sleep. I still have no idea what I’m going to do about Daleville, but if I push it I can make Daleville, resupply, and be on my way to the shelter after if nothing pans out.

September 18

(18.5; 1459.7 total, 714.3 to go; +3.5 from pace, -70.3 overall)

I wake up early to head out and start hiking…or rather, I’m woken up early. Unexpectedly, out of nowhere, comes Medicine Man for an early-morning stop, and shortly behind follows Smoothie. Hmm…this could be the answer to where to stay tonight! Medicine Man remarks that I must have sped…up, in order for him to have seen me again (he’s still hiking, stopping off-trail for a bit, then continuing again). I quickly pack up, pop a Pop-Tart, and head south with them.

Hiking goes well today; we tend to take a break about every hour or so, with fast-paced hiking in between. My pace now seems to be almost the same as Medicine Man’s on flat terrain. Heading uphill he moves noticeably faster than either Smoothie or I do; downhill we make up what we lost to him on the uphills. We stop at Wilson Creek Shelter and regroup as Cubby, Spoon, Santana, and the rest of that group also pass by, then again at Fullhardt Knob Shelter a handful of miles out of Daleville. The shelter has a unique water source based on retaining runoff from the roof in a well. I skim the register and make some offhand comments about entries, including one by the Four Sisters, and someone else says they didn’t complete the trail — and even stranger, they decided this halfway into the 100 Mile Wilderness after hitting a lot of rainy weather. It’s true there were also college deadlines in play, making it necessary to keep an accelerated pace to finish — but still, I can’t imagine what would possess someone to walk 2100 miles and then give up with only 75 to go. (I hear they did have plans to reunite to finish out the trail in summer 2009, but I don’t know whether or not it actually happened.)

We arrive in Daleville by early afternoon, Smoothie and I slightly ahead of Medicine Man because the last five miles from the shelter include more downhill than flatland or uphill. The three of us split a room at the Howard Johnson’s just a few hundred feet down the road the trail crosses in Daleville. Since it’s still fairly early in the afternoon there’s lots of time to relax. I get a shower, laze around a little, resupply on groceries, head across the street to a Mexican restaurant for dinner, and return in time to catch a college football game Medicine Man in particular is intent on watching. A good day all around…

Thirty-seven days, just under a third of the trail’s mileage to go…