Yesterday I discussed offensive speech, especially relevant to the Texas license plate situation because the design’s being seen as “offensive” was Texas’s justification for denying Texas SCV‘s request. Today I talk a bit about oral argument.

Government speech

Texas hammered on its government-speech argument, but it generally didn’t get a very receptive audience. As Lyle Denniston observed, most of the justices’ questions and comments implicitly assumed there was a free speech issue to determine — which wouldn’t be the case if Texas SCV’s design were government speech. I doubt there’s more than a vote or two for these plates being government speech, if that.

One particularly gratifying discussion of government speech occurred when Texas’s advocate attempted to assert the specialty license plates were government speech because of the level of control, and Justice Kennedy noted the circularity of the argument. It was good to see practically the first problem I noticed in Texas’s argument, was also noticed on the bench. Chief Justice Roberts’s expression of skepticism about the program having no clear, identifiable policy being articulated, instead stating Texas was doing it for money (later joined by Justice Alito on the latter point), was also welcome.

A fair bit of time was spent discussing hypothetical “Vote Republican” and “Vote Democrat” license plates, and whether a state might approve one and deny the other. It’s not clear to me (nor was it clear to the justices) that “government speech” would directly prohibit this, but various “independent rules” were observed that would prevent such (just as such electioneering would be prohibited, somehow, in official ballots).

Forums

As I suggested earlier, Texas’s specialty plates program seems to be either a designated public forum or a limited public forum. Justice Kennedy picked up on this, asking if this was a case where Texas had opened “a new public forum in a new era”. Justice Alito posed multiple hypothetical questions involving government-established places where speech might occur, and the implication I drew from his comments suggested that he also viewed such cases as public forums. Each justice also presented hypothetical cases where the government set up a place for speech to happen (a billboard with a state message on it, with a small space for private speech to take place; officially-designated soapboxes in parks), then questioned whether it could be government speech or instead a public forum.

Justice Alito also probed the nature of the license plate forum if the state accepted only colleges, then colleges plus scenic places, and so on, gradually expanding into everyone. The point being: at what dividing line is a scheme no longer government speech? Texas SCV’s answer was that every state-designed plate would be government speech — but plates designed by private entities would be those entities’ speech.

“Offensive” speech

Various justices expressed concern that approving Texas’s denial might lead to regulation of offensiveness in other forums. Justice Ginsburg characterized the “might be offensive” standard as “nebulous” and granting too much discretion. Justice Kagan worried about approval of regulation of offense spreading into more and more forums, producing more and more regulation of speech.

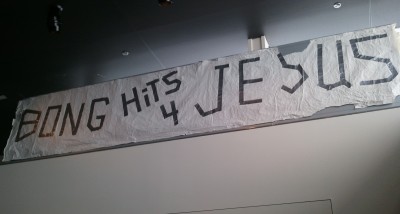

The true fireworks for offensiveness, of course, arose when Texas SCV’s free-speech nut lawyer rose to defend their position. In essence he argued that once Texas extended an open invitation to anybody, they no longer could control what was said. Then, in response to successive questions, he argued Texas couldn’t prohibit license plates with swastikas, “jihad” (which he initially misheard as “vegan”, to laughter), “Make pot legal”, “BONG HiTS 4 JESUS” (more laughter, and a high point of the argument), and ultimately “the most offensive racial epithet that you can imagine”. Truly it was a glorious display of zeal for freedom of speech.

Selectivity

Various justices also made comments as to Texas’s non-selectivity in approving plates. Texas approved over 400 plates and rejected only around a dozen. Clearly several justices thought that near-blanket approval weakened any argument Texas might have for the state carefully exercising discretion in every instance, and strengthened the argument that they’d opened up a public forum for speech.

Those are some of the high points of argument. If you’re interested in more detail, see the transcript.

Next time, it’s probably on to a series wrapup. But no promises yet, as I haven’t written up enough thoughts to be certain. And again, as I noted yesterday, this might end up delayed a day or two. Til next time!