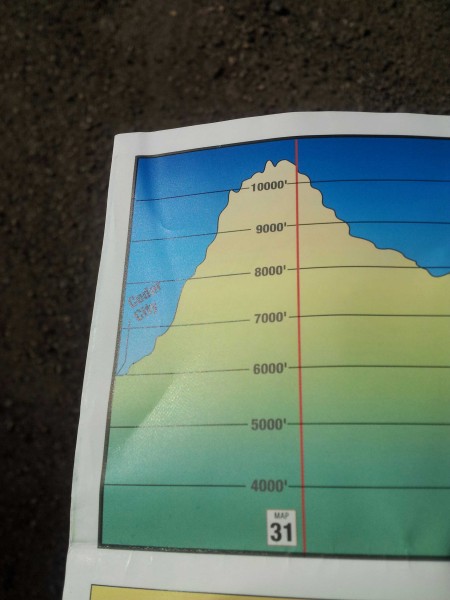

This is part ten of a series of posts discussing various aspects of a bike trip I did across the United States in 2012. Part one discussed the start of the trip and choosing a route. Part two discussed my daily routine and nightly shelter. Part three discussed general mileage, elevation encountered, and state-by-state scenery. Part four discussed mileage extremes and water. Part five discussed food. Part six discussed elevation extremes, particularly crossing the Continental Divide at Monarch Pass. Part seven discussed how I used down time and how I kept electronics charged. Part eight discussed mechanical problems and other surprises. Part nine discussed health on an aggressively-paced cross-country bike trip. This post discusses how I managed to get home afterward.

Arranging the flight

I put off buying a plane ticket home for approximately as long as I could, to afford myself the most flexibility in returning. I had a firm deadline of August 23 (or maybe the morning of August 24, but that would really be pushing it) to finish, because some friends were getting married in Golden Gate Park on August 25, and I didn’t intend to miss it. (This would cut it close timing-wise, but as long as I knew sufficiently far in advance, it seemed doable.) If by some chance I finished early, it might be worth biking to some particular airport to fly from there. If by some even less likelier chance I didn’t finish, I would need to fly from whichever airport happened to be closest.

On Monday, August 20, I found myself by a library, before lunchtime (so with considerable time left in the day to bike) with ~420mi to go in 3.5 days. With the end comfortably in sight, it seemed safe to book a flight. Yorktown’s poorly situated for getting to any major airport, so I’d have some fun leaving it. But unlike excess distance between me and Yorktown, this problem could be relatively simply solved with a large infusion of cash. 🙂 So I didn’t sweat arranging a return flight before then, and I booked a flight from Norfolk to San Jose (with only a single stop along the way) on Southwest, leaving mid-afternoon August 24. The cheap tickets were all gone by then, of course, but my fare did get me a drink coupon on each leg as a consolation bonus. 🙂

Travel-day frenetics

I arrived in Yorktown just before 19:00 on August 23, giving plenty of time to get a bite to eat and clean up to head out the next day. I called one bike shop in town to ask about packing up my bike the next day for travel (justifiably oversized luggage, but a bargain at ~$50 with Southwest). They didn’t know if they had any boxes of the right size in stock, so I decided next morning to head to the other nearby bike shop instead.

The next morning I packed up my stuff and hopped on my bike one last time to head to the Yorktown park headquarters, as an easily-found location for a taxi. (I could have biked to Norfolk, but not easily in time for a flight. Plus I’d still need to get my bike packed up and I’d need a shower.) Yorktown’s way at the edge of the Norfolk taxi coverage — it took just under half an hour for the taxi to even get to me. The next stop would be the other local bike shop. On the way I mentioned my plans — to wait for the bike to be packed up, then to head to Norfolk and the airport. This worked out pretty well, because the driver noted that I was still pretty far away from taxis, so it’d be fastest to just call her again. I pocketed a business card to make the call when the bike was packed up.

On talking to the bike shop folks, I realized I had a slight problem. The bike shop would be perfectly happy to box up my bike for me, but they couldn’t do it today: they were already booked as far as work went. Hmm. They did have a spare box and tools, if I wanted to pack up the bike myself. But I was slightly pressed for time, on vacation, and not particularly interested in packing my bike myself. As it happened, however, the bike shop I’d called the previous day (that wasn’t sure if it had any boxes of the right size in stock) didn’t have a box but did have time to pack a bike. By our powers combined, I could take the bike box here to the other bike shop, and I could get my bike packed up there. Win!

So I called the taxi again, we took the box to the other bike shop, I had them pack it up, then I headed to the airport and my flight. The timing was close but not razor-thin, and I had something like half an hour’s wait at the airport before my flight was scheduled to board. (It’s a good thing I booked the last flight of the day heading west! But it seemed foolish booking any of the earlier ones, given that I’d have to travel forty miles from Yorktown to Norfolk and deal with the bike along the way.) I got a few funny looks at airport security when I sent my shoes through the scanner: metal cleats in the soles will do that. 🙂 A couple flights and a bunch of reading later, I was in San Jose, only a short ride (not on the bike, from a friend 🙂 ) from home.

Hindsight is 20/20

Looking back it’s obvious what I should have done for that last day: I should have called a couple weeks or so in advance, told them my plans, and had them clear a spot to pack a bike when I arrived. Some part of me unconsciously resisted doing this because of the uncertainty of my travel plans, I’m sure. But it seems unlikely it would have been a problem to call, make that uncertainty clear, and then give a call a couple days out with the go/no-go signal as needed. But in the end, it all basically worked out. And even if it hadn’t, these were problems that — again — could be solved, if absolutely necessary, with a large infusion of cash. As a true last resort, I’m sure I could have found someone to pack and ship the bike for me, while I flew back home separately. It would have been more than a bit inconvenient and more than a bit expensive (I’d guess at least $100 more, but that’s just a guess), so I’m glad I didn’t have to do it. But it would have been doable, if I had to.

Naming and faming

It took a fair bit of composed scrambling (I was reasonably composed, tho I’m sure others would have freaked out 😉 ) to make all the connections that last day. BikeBeat was the bike shop that couldn’t box my bike up but could provide a bike box; a different BikeBeat happened to be the ones that suggested the previous day that I could probably bike to Yorktown with two broken spokes (and that gave me a number to call if I broke a third en route). Back Alley Bikes was the bike shop that could box my bike while I waited but couldn’t provide a bike box. And last but not least, Karen (1-757-503-0657) shuttled me around to the different bike shops and then to the airport, going out of her way (literally, to Yorktown 😉 ) to do so. (And when it came time to swipe a card and pay with Square — she informed me she was one of, if not the, first drivers at the cab company to accept credit cards, that way — I didn’t even hesitate to pick the 35% tip option. Totally justified, totally worth it.)

Next time, the gear I used on the trip.