I tend to take either relatively brief vacations (a day or two at a time) or very long ones. Brief vacations serve specific purposes, so they only mentally recharge me a little. Only long vacations let me set my head straight. Recent long vacations have been:

- 2008: thru-hiking the Appalachian Trail, over nearly five months;

- 2010: thru-hiking the John Muir Trail, over two and a half weeks;

- 2011: hiking/walking/pub-crawling the Coast to Coast Walk across northern England with my dad, over a few weeks;

- 2012: biking across the United States, over thirty-seven days;

- 2014: biking from the Bay Area to the eastern end of the Phoenix metro area for my grandma’s 90th birthday, over eight days.

I haven’t taken any long trips to unwind since 2014. Injuries (a persistent high ankle sprain ultimately requiring arthroscopic surgery, a stress fracture to the same foot) are partly to blame. Regardless, I haven’t fully decompressed in a very long time.

During the last weeks of the A.T. thru-hike, I stayed at a hostel with a Pacific Crest Trail thru-hiker guidebook. When I finished reading it, I knew I would hike the PCT. I wasn’t sure when, but I knew it would happen.

This year’s the year.

Conventional wisdom holds that if you can hike the ~2175mi A.T. in N months, the ~2650mi PCT will take N – 1 months. (The A.T. is a rugged trail of rocks and roots; the PCT is a well-graded horse trail.) Obviously this breaks down eventually, and I suspect a relatively-fast 137-day A.T. pace passes that point. I’m guessing I’ll need four months: 240 hours of PTO (Nᴇᴡ Hɪɢʜ Sᴄᴏʀᴇ!), then three months’ unpaid leave, including a cushion. I’m guessing I’ll be done by mid-September.

The A.T. is generally non-technical. No special equipment is required (except during snow extremes at the north end). Civilization is almost always nearby. The PCT is more technical, with a trail unmarked by omnipresent white blazes or signs regularly identifying the PCT. Lingering snow may completely obscure the trail. Swollen, icy creek crossings present dangers I only approached a single day on the A.T. Resupply locations are less frequent and comprehensive. It’s necessary to mail food to oneself at certain points, to resupply at all at them.

The learning curve for the PCT is steeper than for the A.T. Some people might worry about this, but I won’t be one of them. Worrying isn’t helpful: why allow it take root?

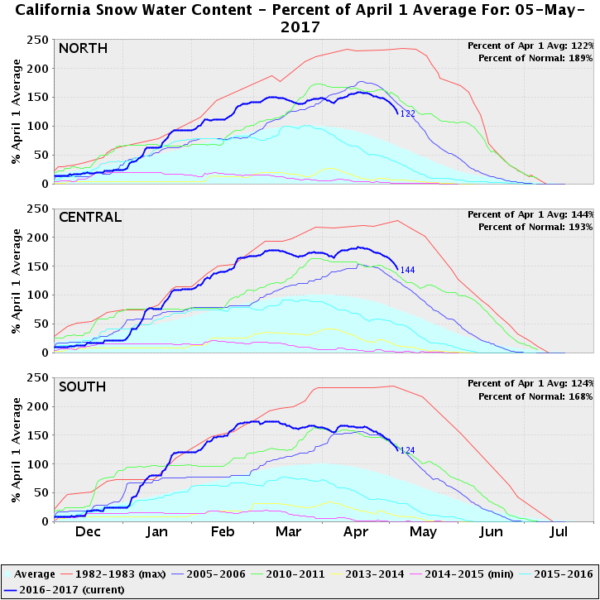

Caution and preparedness are different matters. For example, I know ~zero about safely hiking through alpine snow. And this year was a roughly every-six-year snow year, maybe worse in localized areas. But I can address that with training. There should be room to learn other PCT peculiarities in the first few hundred miles.

My only uncontrollable concern is that foot stress fracture. It happened two and a half years ago; the fracture has healed; and I’ve walked, run, and hiked on it for a year. A sports medicine doctor cleared me to walk to Canada on it. (I was very specific about doing exactly that.) But my right big toe still isn’t 100% flexible, its ligaments semi-regularly ache during or after exercise, and it sometimes bruises. I’ll do what I can about this through cushioned socks, ongoing flexibility exercises, and moderating pace if needed. But I can’t eliminate the risk that it might significantly slow me down or even stop me.

If all goes well, I’ll return in September, mentally refreshed, with a peculiarly developed endurance for walking and very few fast-twitch muscle fibers. 🙂 I’ve turned off Bugzilla request capabilities, so don’t try asking me to review patches. If you must contact me, email might work. I’ll rely heavily on server-side filters to keep the firehoses hidden, but that doesn’t mean I’ll necessarily see an email. If possible send reviews and questions to the usual suspects. Moreover, the PCT is much more remote than the A.T., so I’ll likely go longer between email access than I did on the A.T. In places, a two-week delay in responding would not be unusual. (But I’ll try to keep people updated on where I am whenever possible, specifically to reduce the risks and dangers in a moronically-avoidable 127 Hours-style rescue snafu. I put the best odds on Twitter updates because they’re quickest. But I’ll post some pictures here as well to one-up roc. “My country’s scenery beat up your country’s scenery”)

I’m currently on my way to San Diego. Some helpful souls who love the trail (“trail angels”, in the vernacular) offer aspiring thru-hikers a place to stay just before, and a ride to the start the day of, their thru-hikes. I’ll stay tonight with them. Tomorrow the rubber hits the trail. It should be good.